Mesoamerican Languages in Oregon Event

Remove vaccine barriers for Latinx communities

Episode 6: Still Here: Black Farmers & Agricultural Stewardship in the Modern Age

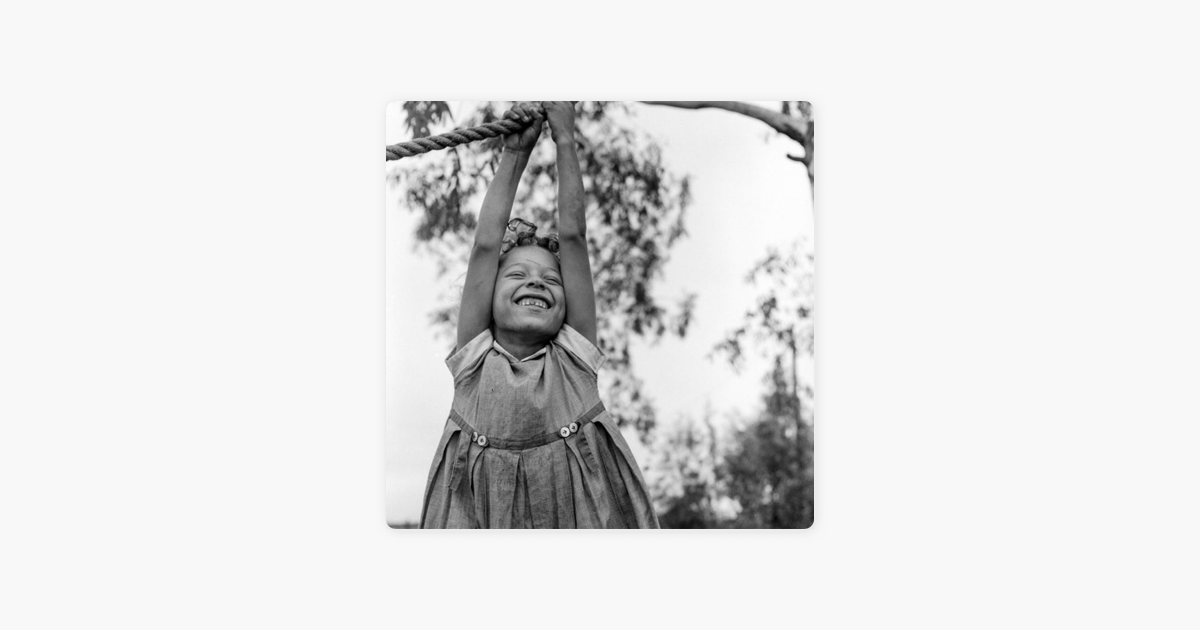

Relationships to the land can be seen throughout African American history and culture. However, Black Californians haven’t just long been connected to the natural world in the past.

Photo: Will Scott Jr. at work on his farm, 2015. Credit: Alice Daniel/KQED.

Music Credit for Episode 6: “Strange Persons” by Kicksta; “Summer Breeze” and “Inward” by HansTroost; Woke Up this Morning-Jazz Organ (ID 1293) by Lobo Loco. Tribe of Noise licensing information can be found here: prosearch.tribeofnoise.com/pages/terms

Never miss an episode — subscribe today:

Transcript We Are Not Strangers Here Episode 6

“Still Here: Black Farmers & Agricultural Stewardship in the Modern Age”

Caroline Collins (Narrator): When people imagine Black Californians in the modern age they often think of them living in urban spaces disconnected from nature. And while the majority of African Americans in the state do reside in cities, their relationships with worked land has survived and thrived in urbanity.

In fact, successive generations of Black migrants adapted to city life by establishing ways of living that often preserved their relationships to the land. So much so that–

Susan Anderson: This idea that Black people are somehow separated from nature and wilderness is really peculiar. When you think about how often the opposite is really true.

Caroline Collins: Because what is true is that African Americans across the state brought agricultural traditions to the cities where they settled, maintaining practices that many of today’s urban farms continue.

And this Black agricultural stewardship isn’t just happening in urban environments. Today, at farms and ranches across rural California, African American farmers are working to carry out the legacy of generations of Black agriculturalists who worked the land for centuries.

Will Scott: The original farmers in this country was African American. We got away from it but we are coming back to it.

(Cal Ag Roots Theme Music, upbeat jazz hip-hop fusion)

Caroline Collins: So, as we’ll soon discover, not only have Black Californians long been connected to the natural world, their connection continues to this day.

In urban and rural spaces across the state.

–Small pause–

Caroline Collins: I’m Caroline Collins and this is the Cal Ag Roots podcast. Cal Ag Roots is unearthing stories about important moments in the history of California farming to shed light on current issues in agriculture. This is the sixth and final episode in our We Are Not Strangers Here series. This series, which draws its name from writer Ravi Howard, highlights hidden histories of African Americans who have shaped California’s food and farming culture from early statehood to the present.

This six-part series is also connected to a travelling exhibit with the same name. The exhibit was originally designed to travel throughout California–we printed big, beautiful banners full of all kinds of photos from the archives that accompany the stories we’re telling. But then, the pandemic happened. And so, now we’re digitally reconceiving the We Are Not Strangers Here exhibit so that people can still enjoy it even during the pandemic. It’s not up yet, but we’re working on it. Please check out www.agroots.org for updates.

(Music ends)

PART ONE: CITY GARDENING

Caroline Collins: Throughout this series, we’ve discussed the many ways that Black people have impacted the landscape and culture of rural California. From gold miners to homesteaders to agricultural laborers, African American settlers have made their mark on the Golden State even before its inception. They farmed and they ranched. They developed agricultural innovations like new irrigation methods. And they established communities, towns, and settlements across rural California from the Central Valley to the Oregon border to the southern reaches of the state.

But Black people in California generally aren’t associated with nature, despite this legacy. As we stated in our opening, part of this misunderstanding has to do with the fact that today, many African Americans reside in urban areas. But as we just mentioned, plenty of Black migrants incorporated agricultural practices into city living. So why is it that urban Black folks are so often seen as completely disconnected from the natural world?

To understand this misconception, we need to start with an important American myth. It’s a myth that shapes our understandings of wilderness and civilization and it’s one that’s changed over time.

–Small pause–

(Pensive orchestral music)

Caroline Collins: In the early stages of American colonization European settlers often saw themselves as bringing productiveness, order, and civilization to a wild environment. In fact, in their view, this process was key to the birth of the nation. These ideas about what civilization did and did not include have had lasting impact. And as scholars like Kevin DeLuca and Anne Demo point out, over time those who weren’t considered part of Wwhite civilization got quote “coded as nature.” John Muir, for example, who’s known as the Father of the National Parks system, operated from a perspective where, in his view, Indians were a part of nature and not human agents that transformed it.

However, this national desire to transform nature into civilization didn’t last forever. With the expansion of industrialism, wilderness spaces increasingly became viewed as places that needed protection. This shift in perception also impacted racial understandings of nature.

For example, by the beginning of the 20th century there was what environmental history scholar Carolyn Merchant called a decided “whitening of the wilderness” by Wwhite conservationists. This meant that they viewed the natural world as no longer a place to be settled or even lived within. Instead, in their view, nature was meant for conservation, recreation, and tourist consumption–primarily by Wwhite Americans. It was an imagining that in many ways took Native Americans–who’d once been viewed as nature–out of perceptions of wilderness.

And as African Americans increasingly moved to urban environments, portrayals of Black people’s relationship to nature also changed. In fact, according to Merchant, by the late 19th century it was the city that many Wwhite Americans viewed as a quote “dark, negatively charged wilderness filled with Blacks and southern European immigrants, while mountains, forests, waterfalls, and canyons were viewed as sublime places of white light.”

Caroline Collins: This re-imagining of place and race meant that dominant cultural stories associated Black people solely with urban places–urban spaces that were seen as completely disconnected from nature. Or as writer Ravi Howard puts it in his essay “We Are Not Strangers Here,” quote: “At some point the terms urban and black became interchangeable.”

So given this misconception, we talked to historian Susan Anderson, our podcast’s Primary History Advisor and the History Curator and Program Manager of the California African American Museum to get a fuller picture about how Black folks actually lived in urban and suburban spaces and the ways they stayed connected with nature. And she reminded us of a long and significant history regarding Black people and gardening–one that dates back centuries.

Susan Anderson: The land can be seen throughout African American history and culture. It goes all the way back to the remnants of cultures in Africa that were brought here by an enslaved people bringing practices from cultures where the cycles of planting and reaping were part of the rhythm of life.

Caroline Collins: These practices which were maintained by enslaved people, even under duress, often centered around the cultivation of small patches of land. So–

Susan Anderson: Gardens even in slavery were very vital to Black people for their own subsistence and survival.

Caroline Collins: Sometimes these gardens were located next to cabins of the enslaved or they were tucked away in nearby hillsides, swamps, and forests. But regardless of their location, they were central parts of the lives of enslaved individuals throughout the Americas. Because it was in these spaces that enslaved Africans and their descendants quote “‘stole’ back their own time and labor in snatches of the night, on Sundays or ‘holidays.’” That’s according to Brown University’s Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, which actually reconstructed a slave garden on its campus.

So these gardens were essential. And they provided many things, including–

Susan Anderson: Self-sufficiency…we ate everything out of our garden except the, the flowers and other plants that meant a kind of beauty…

Caroline Collins: And that beauty was just as important. Beyond sustenance, these gardens–even during slavery–were also spaces of physical and spirtual refuge.

Susan Anderson: Even under those circumstances, they were places for leisure and enjoyment

Caroline Collins: Where they offered–

Susan Anderson: A kind of contemplative approach to life and solitude.

Caroline Collins: These practices of carving out and nurturing whatever small space of land was available for cultivation, contemplation, and rest survived even after enslavement.

Susan Anderson: You can see that carried on through freedom and through modern times and through the 20th century and vernacular gardens in the kind of ornamentation that city gardeners would express.

Caroline Collins: In fact, these city gardens would continue to play an important role in the lives of Black Americans–even in California.

–Reflective pause–

(Music ends)

Caroline Collins: By the mid-twentieth century, many African American residents in California followed national trends, moving from the country to the city.

Not only did some Black Californians relocate to cities from rural areas within the state during this time. Part of this urban concentration was also due to what’s known as The Great Migration–a migration we talked about in our second episode.

It’s an important part of state history, so here’s a quick recap. Even though Black people have been settling in California since Spanish colonization and though Black folks took part in the gold rush and homesteaded in the 19th century–It’s the Great Migration that is most often mentioned in historical accounts of Black settlement in the Golden State.

During the Great Migration, between 1915 and 1960, five million Black Americans left the South. Historical narratives that discuss this migration often explain how many of these migrants settled in Northern and Midwestern cities like Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and New York. But many of these new settlers also headed West. They started new lives in Denver, Portland, Seattle, and Phoenix. And in California they came to cities like San Francisco, Oakland, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

Urban Politics Scholar Dr. Lorn Foster examines Black migration to Los Angeles in the first half of the 20th century. He explains how by the mid-twentieth century Black Californians weren’t just living in urban spaces, they were increasingly leaving previously steady work in personal service and small business for more lucrative opportunities in industry.

Lorn Foster: It’s only with the outbreak of the second world war that you see this movement toward industrial jobs in African Americans in Los Angeles and in Oakland, in San Francisco.

Caroline Collins: But even with growing concentrations of African Americans in urban environments and increasing industrial employment, Black Californians continued to value agricultural practices. So they brought practices to cities through–

Lorn Foster: Lots of truck gardens, people raising chickens and eggs.

Caroline Collins: These home gardens and sometimes the raising of livestock and poultry were an integral part of many urban dwellers’ lives in the city.

Lorn Foster: For African American arrivals was an opportunity to be somewhat self-sustained.

Caroline Collins: It’s an independence that retired educator and business owner Eugenia King Bickerstaff recalls with fondness.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: We had that freedom where we could roam around and go and see our friends and get on our bikes and go ride where we wanted to, play out in the street.

Caroline Collins: Eugenia grew up in mid twentieth century Southern California. But she spoke to me via Zoom from her home in Washington, DC.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff : I was born in San Diego and spent my entire life there up until 1972 when I married. And then, moved back East. I was educated at the University of San Diego. I received a undergraduate and master’s degree there in education and began my teaching career there in San Diego.

Caroline Collins: Like many Black residents in her urban community, Eugenia’s parents Alonzo and Verna Lee King were originally from the South before they–

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: moved to California from Louisiana as part of the Ggreat Mmigration.

Caroline Collins: Alonzo arrived in San Diego in 1941 and Verna Lee, just a few years later. Alonzo King was a college educated man who back home in Louisiana had been a principal of a Black school.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: But when they got to California before the Ssecond Wworld Wwar those opportunities were not there for Black folks.

Caroline Collins: So her father picked up work where he could.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: He had several jobs, none of which had anything to do with his educational background, but he did what he had to do in order to provide for us.

Caroline Collins: And in doing so, he provided Eugenia and her siblings with a 1950s childhood that she recalls as downright idyllic.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff : Looking back at the childhood that we had, the sense of innocence. We basically walked everywhere. The Black community in San Diego looked out for one another.

Caroline Collins: So much so that not much escaped their parents.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: We would always laugh as we got older, say in high school, you know, that if we were seen walking down the street and holding hands with somebody, we couldn’t even get home before the word was there.

Caroline Collins: Even with the community’s sharp eyes upon her, it was a childhood Eugenia loved and one filled with memories of the outdoors.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: I think about all the opportunities that we had, everything was free, you know, just being able to go to the zoo and we did it we took advantage of all of that. And we spent a lot of time on the water.

(50’s upbeat organ music)

Caroline Collins: A lot of that outdoor time was a family affair.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: My dad, especially, he loved taking us out to the beach and having those all day cookouts.

Caroline Collins: Her father took his outdoor cooking very seriously.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: Daddy always kept that spray bottle because you kind of had to control those flames. He was a real, uh, artist when it came to being outside.

Caroline Collins: And it wasn’t just the beach. In California, Alonzo King continued a relationship with the natural world that he’d established in his native Louisiana through a variety of activities like hunting and fishing.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: One thing about Ddaddy, he saw comfort from simple things. He loved to fish. He enjoyed being on that lLake and he would take us along and, you know we’re making all this noise and scaring the fish and doing just about everything else that that we could do to be a distraction. But we look forward to those fish fries because we got home Ddaddy was going to clean those fish and get that cast iron skillet going.

Caroline Collins: Looking back, Eugenia realizes there was another element to all of these family adventures. Something much more practical.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: The things that we just thought were like outings and just fun, really the greater purpose was to have a meal that night.

–Small pause–

(Music Ends)

Caroline Collins: Central to these practical traditions that Black Californians like the Kings brought to urban centers was the keeping of home gardens.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: That’s what Bblack folk did. They had some kind of garden going on and just about everybody had a lemon tree or some kind of citrus tree. And if it wasn’t a produce garden it was flowers. And they maintained beautiful yards and took a lot of pride in that.

Caroline Collins: Pride that was often rooted in complex understandings of the natural world.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: My aunt she lived in that area too. Alice Whaley. She had every kind of fruit tree you could imagine. She could identify anything. We look at something and think it was a weed and she would give us the correct name for it and tell you what it was used for.

Caroline Collins: Eugenia’s father also kept a flourishing garden.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: When it came to, to the garden and the yard that was his thing. He had a real feeling for the land.

Caroline Collins: It was a relationship with the land that provided a bounty for his family. In his vegetable garden Alonzo King grew corn, peppers, beans–produce that regularly made its way to the Kings’ dinner table.

(Orchestral folk music)

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: One thing he always had was great collard greens, and you could count on him having a pot of those going on every weekend. We always said, mama was the gourmet cook. And so her, her style of cooking was totally different. Daddy just cooked that good old soul food. That everyday is stuff that you like to have. And lots of Mexican food too, because, you know, we thoroughly were raised on that.

Caroline Collins: Like other Black urban families, the Kings’ home garden wasn’t just a source of sustenance, it was also a site where their private and public lives mixed.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: They would entertain out there. And that was just common with the people that we knew and that California climate, you couldn’t help it be outside.

Caroline Collins: These outdoor forms of entertainment often represented more than simple leisure. For example, in the 20th century, some women participated in garden clubs that were offshoots of African American women’s clubs, and part of a Progressive Era-inspired city beautification movement. And sometimes home gardens even provided the backdrop for key political gatherings. Eugenia remembers one such occasion organized by her mother, Verna Lee, who was heavily involved in local politics.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: I was in kindergarten, then it was only a half day. And I came home and there were all these people in the backyard. You know, these women, everybody was dressed up mama including, you know with hats and the gloves and she was serving and they had the China and the coffee cups and all of that.

Caroline Collins: And it turns out it wasn’t just any run of the mill gathering.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: It was actually a fundraiser for the person who actually became a governor, California, Pat Brown.

–Small pause–

(Music Ends)

Caroline Collins: Reflecting on the role of their family garden, Eugenia acknowledges the agricultural stewardship practices that her parents passed along to her.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: I knew that no matter where I was, I was going to have to have a little piece of dirt somewhere that I could just put my hands in and get them dirty. And I might not have had been growing vegetables and things like that, but I definitely had flowers going on, just trying to create something that was beautiful and that I could enjoy doing and looking at and appreciating my efforts.

Caroline Collins: An appreciation she now understands must have also been a comfort to previous Black city gardeners like her father Alonzo King, who packed up and moved to California in 1941. Who was initially denied opportunities to use his education to provide for his family. But who, despite these circumstances, found a sense of serenity in his backyard urban garden.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: I think that for him, it was relaxing, that’s where he was able to kind of deal with things that were going on around him and just find some peace and some comfort.

(Orchestral folk music)

Caroline Collins: A practice and a space that offered him comfort…into his old age.

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: That spot was a place where he would go, he’d take his radio out there. He listened to a baseball game or smoke a cigar, but he loved that area so much. And just always spent so much time out there. And he actually died in that space. So I take comfort in that, knowing when he died, he was someplace where that he loved, you know, and that’s how important it was to him.

–Reflective pause–

(Music ends)

PART TWO: STILL HERE, RURAL FARMING TODAY

Caroline Collins: The legacy of these Black city gardeners continues today. Across the state, urban farms like Sacramento’s Yisrael Family Urban Farm, Oakland’s Acta Non Verba, and The Ron Finley Project in Los Angeles all continue this legacy by connecting city residents with the earth. They provide fresh, nutritious produce; cultivate green spaces; and promote community cooperation.

However, it’s important to note that African Americans also continue to farm in rural communities across California. Supporting these ranchers and farmers are organizations like the Fresno-based African American Farmers of California, or the AAFC, which is led by Will Scott, Jr. of Scott Family Farms.

He was born into a farming family that migrated from South Carolina, Texas, and Oklahoma to California where they worked in grape cutting. Mr. Scott, however, didn’t originally set out to also become a farmer.

Will Scott: Most African Americans was told to get away from farming because of the slavery connotation. So I got an education.

Caroline Collins: But the land never stopped calling him.

Will Scott: I think when you develop a love for the land, you know it’s there. So when I retired from the telephone company, I jumped out of the skillet into the fire. I became a farmer and farming, as you know, is hard work, you have to love it to do it. But Afro-American has to play a part in this agricultural system.

Caroline Collins: For Mr. Scott, playing a part meant organizing. He began the AAFC which runs a demonstration farm for new farmers–helping them get hands-on experience growing a variety of produce, including Southern specialty crops.

He’s also invested in this work because, for him, understanding and appreciating the cultivation of food is in many ways to understand humanity. Or as he puts it–

(Orchestral folk music)

Will Scott: In the beginning when man, all he did every waking hour was looking daylight hours, looking for food at night. He spent time hiding from the man who or the animal was looking for him for food, you know? So when Man found that, that there are places he could go and there was food, he was able to sit there and stay for awhile. When you eat and stuff like that, you sit around in a group of people love, things come up, you start discussing business, you start talking politics and all that other stuff.

Caroline Collins:: So, he considers supporting the work of small farmers and the food they produce as a moral imperative.

Will Scott: The moral values that exist in this country, whether you own a farm or you and you’re in a big corporate office, those more values originated from the farm. So we have to work out a way to sustain that we have to work together. To sustain the small farmer because that’s a way of life.

–Small pause–

(Music Ends)

Caroline Collins: Sustaining small farmers, however, isn’t always easy.

Gail Meyers: It was like you’re doing rescue work, right. That’s what it felt like. Just always coming to the rescue.

Caroline Collins: That’s Dr. Gail Meyers. Her non-profit Farms to Grow Inc. works with African-American farmers and other socially disadvantaged farmers in keeping, growing, and maintaining a sustainable farming enterprise. She explains the stakes of such work.

Gail Meyers: This farmer losing this land, we were putting out fires, we were getting all kinds of requests or connecting to attorneys.

Caroline Collins: Dr. Meyers wasn’t always directly involved in agricultural advocacy. As a cultural anthropologist and Air Force veteran, her earliest interests in farm work began with her dissertation work at The Ohio State University where she researched the history of African American communities in Ohio, interviewing over 100 farmers in the state. Her project initially led her into academia.

But while teaching Public Health courses in race and race ethnicity disease at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, she hit a wall.

Gail Meyers: When I got to Atlanta, I was using terms like agroecology. This was in 2002… and people were responding with faces. Like, what are you talking about? I thought, Oh my God, I can’t do this work here.

Caroline Collins: So when an opportunity in San Francisco presented itself, she moved and shifted her journey, leaving academia for activism in an epicenter of the sustainable farming movement. And once she arrived–

Gail Meyers: Inevitably someone responded with, oh, well there are five organizations that I need you to know about. And there’s two say I can give you their numbers right now, the 10 conferences that are coming up.

(Pensive music)

Caroline Collins: While she found a community of like minded agriculturalists in Northern California, she also realized there was still a great need for work standing in what she calls the gap between underrepresented farmers and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Gail Meyers: Like we have a farmer in Bakersfield and he’s a veteran. But he doesn’t even know how to turn on a computer. So what we do is we pull up the application and I sit with him on the phone and we complete the application, we send it to the farmer veteran coalition.

Caroline Collins: It’s often challenging and complicated work.

Gail Meyers: That’s the purpose, to organize, to make sure that we can make an impact on changing the farm bill and different policies that affect the appropriations of money and who gets what. That requires a lot of energy. You can get blown out.

Caroline Collins: However, it’s work that she sees as critical. Because organizations like hers aren’t just providing assistance with an often overwhelming bureaucratic infrastructure. In many ways, they’re also working to restore faith in an agrarian promise of the Golden State. So it’s about–

Gail Meyers: Creating hope. Someone that they can see that, you know, has a little bit of understanding of a system that can work on their behalf.

Caroline Collins: And that’s a worthy cause because she believes that when you take the time to examine Black folks and their relationship to the land–

Gail Meyers: You see who these people are.

Caroline Collins: And in seeing so many Black farmers up close and personal, the work that they do, and the history they represent–Dr. Meyers has found herself at a new point in life.

Gail Meyers: I want to put my hands into the soil and continue to involve my soul.

Caroline Collins: Because in her nearly twenty years of agricultural advocacy, she and others like her have helped establish a growing pipeline of new farming advocates.

Gail Meyers: Now they’re like 20 different Black farming groups and now we’ve got b=Black farming coalitions and several cooperatives. And now they’re many more folks that are doing education with kids and communities.

Caroline Collins: And so she’s done her part in activism and is now ready to continue the legacy of Black farming in her own very tangible way.

Gail Meyers: It feels like I can go farm now…So the next evolution in how I see my work on the planet is I want to farm…I’m ready to be a farmer now.

–Reflective pause–

(Music ends)

CONCLUSION

Caroline Collins: So, as we draw this six part We Are Not Strangers Here series to its close, what have we learned by highlighting hidden histories of African Americans who’ve shaped California’s food and farming culture?

For Eugenia King Bickerstaff these hidden histories shine a light on an important fact.

(Pensive orchestral music)

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: We’re at home here we’re at home in our gardens and our yards and, they’ve always been in our lives from one degree or another, they may have started out as being something practical that we did to put food on the table, but from there, they evolved into something else. Something that we just enjoy doing and feel good about.

Caroline Collins: And this connection to the land, even for city dwellers means–

Eugenia King Bickerstaff: We are not strangers here. This is part of who we are.

Caroline Collins: It’s part of who Black people are because, as our Historical Advisor Susan Anderson reminds us, African Americans’ relationship to the land has links to a set of long held ancestral practices. Practices in which the most significant parts of life often revolved around communing with the natural world.

Susan Anderson: The first churches for African-Americans the ring shout ceremonies were held in the woods in the forest at night.

Caroline Collins: In fact, nature can even be seen as a symbol of Black people’s resistance.

Susan Anderson: When you think about the runaways people who ran away to the swamps, the Maroons, or the people who ran away to Indian lands, and that turning point in 1850 with the second fugitive slave law, which created the first refugee crisis in U.S. history enslaved Bblack people who were escaping were negotiating with nature, as they fled slavery, they were making bargains.

Caroline Collins: They were making bargains. And they were planting seeds. They were plowing and investing. They were pouring hopes into the land based on the promise of homesteading, of utopian visions of Black settlements and towns, and the city gardens and rural farms where African Americans continue to till the earth in the hopes that future generations will reap a California harvest greater than what they ever could have envisioned for themselves.

(Music ends)

(Cal Ag Roots Theme Music, upbeat jazz hip-hop fusion)

Caroline Collins: Thanks for listening to the Cal Ag Roots podcast. If you liked what you heard, you can check out other stories like this one at www.agroots.org, or on Apple Podcasts. And by the way, if you subscribe and rate this show on Apple Podcasts, it will help other people discover it.

Now some important acknowledgements: We Are Not Strangers Here is a collaboration between Susan Anderson of the California African American Museum, the California Historical Society, Exhibit Envoy and Amy Cohen, myself–Dr. Caroline Collins from UC San Diego, and the Cal Ag Roots Project at the California Institute for Rural Studies.

Our traveling exhibit banners were written by Susan Anderson, our project’s Primary History Advisor. And this podcast was written and produced by me with production help from Lucas Brady Woods.

This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities (Visit calhum.org to learn more), and the 11th Hour Project at the Schmidt Family Foundation.

And finally, special thanks to TED-x which brought us the voice of Will Scott in this episode.

–End of Episode–

Cal Ag Roots Supporters

Huge THANKS to the following generous supporters of Cal Ag Roots. This project was made possible with support from the 11th Hour Project of the Schmidt Family Foundation and California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Episode 5: Back to the Land: Allensworth and the Black Utopian Dream

In 1908, African American pioneers established the town of Allensworth forty miles north of Bakersfield as part of the broader Black Town Movement. Discover how these settlers not only built buildings, established businesses, and planted crops–they also inspired the imagination as they tested what was possible in rural California.

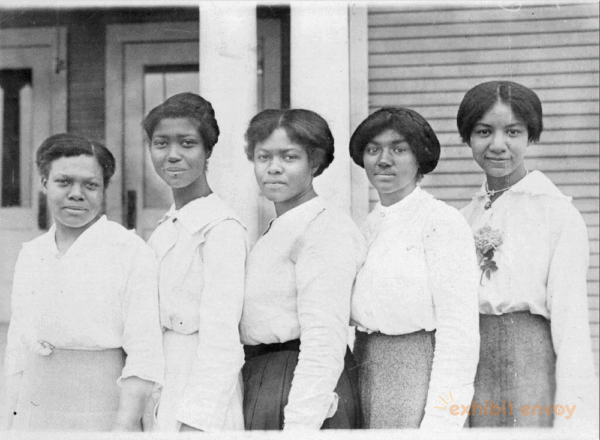

Photo Credit: Teachers at the Allensworth School, c. 1915 [090-2156]. Courtesy California State Parks.

Music Credits for Episode 5: “Strange Persons” by Kicksta; “Summer Breeze” and “Inward” by HansTroost; Over the Water, Humans Gather by Dr. Turtle; “Just Gone” by King Olivers Creole Jazz Band; and The Fish Are Jumping by deangwolfe. Tribe of Noise licensing information can be found here: prosearch.tribeofnoise.com/pages/terms

You can listen online, or better yet, you can subscribe to the podcast so you don’t miss an episode.

Never miss an episode — subscribe today:

Transcript We Are Not Strangers Here Episode 5

“Back to the Land: Allensworth and the Black Utopian Dream”

Caroline Collins (Narrator): The California Dream is an iconic part of the Golden State’s identity. From the 19th century mining 49’ers who dreamed of striking it rich in California’s gold fields, to Hollywood hopefuls longing for fame in the spotlight, to the modern-day tech pioneers wagering for a chance at their Silicon Valley fortune, California has often sold itself as a land of opportunity.

In our last episode, we began a two-part discussion about some lesser-known opportunity seekers: Black settlers who formed communities with one another across California, supporting each other’s dreams of forging independent lives in the state–even when California itself didn’t live up to its promise.

The most well-known of these Black settlements in California is Allensworth. Founded in Tulare County in 1908, Allensworth was one of many Black towns in America rooted in principles that linked land ownership to Black independence.

Steve Ptomey: It is the quintessential American story. People doing what others said they couldn’t do and they’re doing it on their own.

Caroline Collins: And a big part of what they were doing went beyond the physical toll of building a town from the bottom up. In many ways, these settlers were also inspiring the imagination as they tested what was possible in rural California.

Lonnie Bunche: I think one of the powers of understanding Allensworth is that this is really a proactive attempt by an African-American community, not to simply disassociate itself from America, but to be a kind of beacon of hope, a beacon of possibility.

Caroline Collins: In this episode we’re going to finish our two-part discussion of Black settlements in rural California by diving into the history of Allensworth, not just because it’s an important part of state history that often gets overlooked. But because Allensworth also reminds us of the power of the Black imaginary–

Especially around the agrarian promise of ‘returning to the land.’

(Cal Ag Roots Theme Music, upbeat jazz hip-hop fusion)

Caroline Collins: I’m Caroline Collins and this is the Cal Ag Roots podcast. Cal Ag Roots is unearthing stories about important moments in the history of California farming to shed light on current issues in agriculture. This is the fifth episode in our We Are Not Strangers Here series. This series, which draws its name from writer Ravi Howard, highlights hidden histories of African Americans who have shaped California’s food and farming culture from early statehood to the present.

This six-part series is also connected to a traveling exhibit with the same name. The exhibit was originally designed to travel throughout California–we printed big, beautiful banners full of all kinds of photos from the archives that accompany the stories we’re telling. But then, the pandemic happened. And so, now we’re digitally reconceiving the We Are Not Strangers Here exhibit so that people can still enjoy it even during the pandemic. It’s not up yet, but we’re working on it. Please check out www.agroots.org for updates.

(Music ends)

Caroline Collins: As we learned in our last episode these settlements, where Black folks lived with one another, were also often established by Black people. And they generally were in rural California. But they differed in size and location. And they had varying degrees of intentionality. Some were loosely formed by settler preference. Others grew out of exclusion from Wwhite areas or proximity to employment. And many of these communities weren’t self-sufficient. So they were still dependent on the resources and infrastructures of neighboring Wwhite communities.

Allensworth, however, was established with specific aims of self-reliance, like other Black towns that had come before it.

In fact, historian Lawrence B. de Graaf writes that quote “Since slavery [many] African Americans have sought refuge in black communities [and] various towns have been labeled ‘all-black towns’–separate and formal communities established with clear economic and civic intentions.”

And while the economic and political relevance of these towns can’t be overstated, it’s important to also take the time to reflect on their imaginative significance.

(Slow-tempo orchestral folk music)

Caroline Collins: In other words, every Black town established in California–and the nation–first began as an idea. A dream conceived by Black settlers, who, before they ever purchased land, laid blueprints, or raised timber frameworks, they first had to believe that doing so could be possible.

One significant source of inspiration for this imaginative capacity were ‘back to land’ movements led by visionary Black pioneers.

And that’s an important fact to recognize. Because all too often, Black folks in California aren’t associated with lofty ideals about ‘returning to the land.’ Instead, there’s a prevalent idea that the utopian back to the land movement is somehow the purview of Wwhite hippies.

That assumption is especially significant when thinking about the history of Black people in rural California. So this episode acknowledges the longstanding Black imagination about utopian rural life by remembering that Wwhite people weren’t the only folks dreaming up these communities.

We talked to our podcast’s Historical Advisor, Susan Anderson, History Curator and Program Manager at the California African American Museum about the significance of this version of the Black imaginary–one that’s tied to the promise of the land. And she reminded us just how far these kinds of visions extended–sometimes even beyond domestic borders.

For example, in 1918, African Americans in Los Angeles promoted a plan to purchase land south of the border for a settlement they were calling Little Liberia.

(Music ends)

Susan Anderson: It was supposed to be in Mexico, in Baja.

Caroline Collins: The project was led by Hugh Macbeth, a Black attorney who would later play a pivotal role in helping Japanese Americans hold on to their properties after being detained in internment camps. The Little Liberia organizers hoped to establish their all Black settlement just northeast of the coastal town of Ensenada.

Susan Anderson: There was a reason why they wanted to be in Mexico because of escaping racism. They were being welcomed by the Mexican government and the governor.

Caroline Collins: Hoping to initially settle 200 families who would eventually grow the town to 20,000–

Susan Anderson: They worked hard and they traveled back and forth. The elaborateness of the plans were really interesting.

Caroline Collins: But, in the end, these plans never reached fruition. The Mexican government eventually withdrew support due to concerns over racial tensions and the project also faced financial challenges so–

Susan Anderson: Little Liberia never existed but you have to mention it because of the imagination that’s represented.

–Small pause–

(Slow tempo orchestral folk music)

Caroline Collins: However, unlike Little Liberia, many Black towns across the nation did make the leap from conception to construction.

The nation’s earliest Black colonies were actually established in the south during Reconstruction. But by the 1870s, African American pioneers began founding all-black towns across the Western United States as well led by visionaries like Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a formerly enslaved businessman and activist from Tennessee who came to be known as the “Father of the African American Exodus.” At the peak of The Black Town Movement, some colonies drew hundreds of immigrants on a daily basis.

Fleeing racial persecution, these Black settlers established places like: Blackdom, New Mexico, Nicodemus, Kansas, and Greenwood, Oklahoma–home to the “Black Wall Street,” which was one of the most prosperous African American communities in the nation until violent Wwhite mobs destroyed it in 1921, burning down thirty-five city blocks and killing and injuring hundreds of residents.

In fact, it was often Wwhite resentment towards these communities’ intentional independence that made them targets for the very racial violence their residents were attempting to flee in the first place. Despite these risks, Black pioneers established these settlements across the country–including California.

For instance, by the early 1900s, 30-40, mainly landowning, Black families prospered in the farming colony of Fowler. And just four miles away, the quote “colored settlement of Bowles was one of four towns in California cited at the time as being both populated and governed entirely or almost entirely by African Americans.”

And though places like Visalia and Hanford weren’t considered all-black towns, significant num

bers of Black farmers resided there and in other cities in the Valley, establishing cultural institutions from churches to social clubs to an all Black baseball team in Visalia.

Progressive and imaginative, these settlements tapped into a thriving Black imaginary around the promise of rural life. For example, Black people began homesteading in 1914 in Sidewinder Valley, a desert area in San Bernardino County near the African American-owned Murray’s Dude Ranch. And this re-imagining of the rural even impacted forms of leisure. For instance Val Verde, a Black-owned resort that premiered in 1924 in Los Angeles County, gained a reputation as “the Black Palm Springs.”

But, as we mentioned at the top of this episode, of these independent settlements it’s the town of Allensworth in Tulare County that’s perhaps the most well-known. Susan Anderson explains the broader significance of the town.

Susan Anderson: Allensworth is a group of people who said we’re going to create a community that sends this message to the world.

Caroline Collins: A message grounded in Black possibility.

–Small pause–

(Music ends)

Founded in 1908, this all Black town drew more than 200 residents to its utopian vision. That may not seem like much in today’s standards, but for a brand new town in the American West that was a substantial amount. For instance, Tombstone, Arizona–site of the historic shootout at the OK Corral–began with only half as many settlers.

Today a state historic park preserves the history of the town of Allensworth. Steve Ptomey, Chief Interpreter for the California State Parks Great Basin District, oversees the public programs for 11 parks, including Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park.

A trained archaeologist, part of Ptomey’s duties include detailing the life of the park’s namesake and town co-founder Colonel Allen Allensworth, who was born enslaved in Kentucky in 1842.

Steve Ptomey: He was sold down river several times for learning how to read.

Caroline Collins: Col. Allensworth first began learning to read in secret from the son of his original owners, the Starbird family, who also owned his mother Phyllis. When the rest of the Starbirds found out, they didn’t sell Allen, but placed him with another family who were Quakers instead. But then the Starbirds discovered the Quaker family was continuing to teach the bright child and even was allowing him to attend a school for enslaved children. So they took him back and sent him to their relatives further down the Mississippi River in order to put an end to his education. But Allen continued to learn at every chance, in spite of violent repercussions for doing so. That meant anything from whippings to repeated sell-offs, one owner after another.

Steve Ptomey: So he was someone who had an intrinsic desire to learn and to improve his position, not only for himself and his family and of course his people.

Caroline Collins: When the Civil War erupted and Union soldiers neared Louisville, Allen–after two initial attempts–successfully escaped his final owner and joined the Union forces. He served in the U.S. Navy for two years. And after the war–

Steve Ptomey: He goes into the seminary and it becomes part pastor, part educator.,

Caroline Collins: After ministering to congregations around Knoxville and Nashville, Tennessee, Allensworth heard that the U.S. Army was looking for Black chaplains to serve in African American units. He applied to be the chaplain of the 24th Infantry. He was accepted and served for 20 years, becoming the first African American to reach the rank of lieutenant colonel, making him a highly ranked commissioned officer that’s the equivalent of a Commander in the Navy.

Steve Ptomey: Everywhere he went, he established a school in part to make sure people knew the basics of reading, writing and some basic arithmetic. So they couldn’t be taken advantage of.

Caroline Collins: A meticulous man, his lifelong dedication to learning was often evident in his own personal library. He was well read and enjoyed classics. Perhaps in part because of one of his mother’s last acts of maternal care before the Starbirds sent her child away from her:

Steve Ptomey: She gave him some money and said, you know, you go buy a book and a comb and put everything in the book and use that comb to comb everything but knowledge out of your mind. Focus on that. Cause that’s the key.

(Orchestral folk music)

Caroline Collins: His mother had given him all the money she possessed: a silver half dollar. With that, he did eventually purchase his first text: The Webster’s Spelling Book.

–Reflective pause–

Caroline Collins: After retirement, Colonel Allensworth became further interested in Black independence and especially what he saw as the economic, social, and political promise of the West.

(Music ends)

Lonnie Bunch, the founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History and Culture and now the Director of the Smithsonian Institution, has written about Allensworth’s keen grasp of California’s simultaneous promise and constraints. He says that Col. Allensworth came to California

Lonnie Bunch (NPR): Because he’d been there many times with his troop, and was stunned by the discrimination he faced in southern California, and decided, along with four other men, that they would create a colony somewhere in California where, quote, the Negro could be free of prejudice.

Caroline Collins: These four other men were also leaders in their respective communities across the country: Professor William Payne was an educator who because of racist practices was denied a teaching license in Ohio; Dr. William H. Peck was a Los Angeles African Methodist Episcopal Minister; J.W. Palmer was a successful miner in Nevada; and Harry Mitchell was a Los Angeles realtor. Together, they became the core members of a visionary group.

On June 30, 1908, they formed the California Colony and Home Promoting Association–a land development organization with offices in downtown Los Angeles. Their first project was the town of Allensworth, named after The Colonel. Again, Steve Ptomey.

(Pensive music)

Steve Ptomey: Think about the monumental effort it is to create a town out of nothing. You know, it’s not like they have the internet, it’s not like they have contractors that they can just come, Hey, come build this, you know, you build it and they will come. No, he’s going out to recruit people to invest their life savings.

Caroline Collins: They were selling a dream.

Their ‘back to land’ movement was part of a long tradition. One rooted in an agrarian ideal dating back to advocates like Thomas Jefferson who linked lofty goals like independence, morality, and equality to notions of land ownership and agriculture.

In fact, in the eyes of developers to educators like Booker T. Washington, California was fast becoming a beacon for such land-based opportunity. Allensworth promotional materials latched on to this vision, marketing the proposed colony as a community offering quote “corn billowing in the wind” flowing “artesian water…paved streets, and pretty houses by beds of flowers.”

Steve Ptomey: He pitched this idea of being a gentleman, farmer of, you know, eating the fruit from your own trees and picking it for your own benefit, which has had a lot of broad appeal.

Caroline Collins: It was an appealing vision, but one that was difficult to pull off. Unable to purchase enough land to initially sustain a township, the Association entered into a promotional agreement with three Wwhite-owned real estate companies. These companies laid out an initial 80-acre township and they struck a bargain. The Association would bring in the settlers and in exchange the development companies would reserve the land for Black farmers.

The association advertised nationwide in African American newspapers, and in just three years sold more than four hundred parcels of land.

(Ragtime music)

Residents began moving in. They expanded their acreage and established an artesian well system. That meant their wells reached deep water that was compressed and protected between layers of rocks. They planted farms, started businesses, and soon–they had a thriving town.

Steve Ptomey: It had a voting district. It has a school district, a post office.

Caroline Collins: Key indications that the town was actually becoming a town and not just a collection of homes.

Steve Ptomey: It had rail access and had a Telegraph line… And it was a big deal.

Caroline Collins: Because those technologies weren’t just key to the agricultural businesses many Allensworth citizens hoped to launch. Their rail access also enabled them to open a depot station that could serve the wider area beyond their town. And that wasn’t all they built.

Steve Ptomey: They had a full church. Now they didn’t have a pastor that stayed on site. They had a circuit preacher minister that came around.

Caroline Collins: They were missing one major town staple though.

Steve Ptomey: The one thing that you don’t see in Allensworth is a bar. It was a dry community.

Caroline Collins: The people of Allensworth even elected the first African American Constable and Justice of the Peace West of the Rockies though crime in the town was almost nonexistent.

Steve Ptomey: I believe in one of the worst things that they did with Henry Singleton had planned a, a senior prank when he was in the school and they were going to take apart somebody’s buggy and put it on the roof and they got it apart and they got part of the buggy on the roof and then they got caught. So they had to put it back down on the ground and reassemble it again, you know, fairly classic hi-jinks.

Caroline Collins: In other words, it was a classic American town, full of hardworking people looking to ensure a prosperous future for themselves and their children.

–Small pause–

(Music ends)

Steve Ptomey: If you were to look at the material culture of the town, you know, speaking from an archeologist point of view. I could not tell this town apart from any other town in the Valley at the same time period. It had all the earmarks of a town that was going to grow.

Caroline Collins: In addition to the Baptist church, hotel, general store, and schoolhouse, Allensworth also had a blacksmith shop and a barbershop. There was also thriving arts and culture in the town. They boasted an orchestra, glee club, brass band, and the first branch of the Tulare County Library. The founders even had expansion hopes for the surrounding community as well where they wanted to eventually open a polytechnic college, one that would be considered the ‘Tuskegee of the West.’

It was all a thriving enterprise. For many reasons. But especially because the Allensworth founders also had the benefit of envisioning the town during the 20th century, decades into the Black town movement.

In other words, in 1908, when Col. Allensworth and his partners launched the town, they weren’t just joining a long history of strategic African American settlement. They were in many ways looking to push the movement to new barriers.

–Small pause–

Caroline Collins: Dr. Ashley Adams studies preservation policies and planning for African American heritage sites like the National Park Service’s Nicodemus National Historic Site in Kansas and California’s Col. Allensworth State Historic Park. She explains the evolution of later Black towns like Allensworth.

Ashley Adams: Nicodemus, was founded in 1877.

Caroline Collins: Which was some 30 years before Allensworth was established, so–

Ashley Adams: The people of Allensworth were a little bit further advanced than the people of Nicodemus.

Caroline Collins: They were also generally more well off.

Ashley Adams: A lot of them were established already and were educated. You know, one lady moved from Oakland. It was her second home so it was kind of the next level for them.

(Uplifting orchestral folk music)

Caroline Collins: This ‘next level’ included viewing African American colonization not only as a means of escaping persecution, but as a key mechanism for broader structural change. Again, Lonnie Bunch, Director of the Smithsonian.

Lonnie Bunch: They recognized that what they were doing was greater than them. While they definitely wanted to have a community where there could be Bblack business and shopkeepers and school teachers, they recognized that their mission was bigger.

Caroline Collins: It was a goal with national intentions.

Lonnie Bunch: If they could be a successful community and show economic progress, and show leadership, they felt that would be a beacon of change that would echo around the country. That people would see Allensworth and say, African-Americans can control their own destiny, can be contributing members of American society. And their hope would be that it would help to change the racial dynamics in this country.

Caroline Collins: At the core of these dreams, however, was their grounding as an agricultural community.

–Reflective pause–

(Music ends)

Caroline Collins: Before they started farming though, The Allensworth settlers researched cash crops that would have a quick turnover. Eventually, they settled on alfalfa–a choice ahead of its time considering that alfalfa is now the predominant crop of the area.

But it’s also a crop that requires a lot of water. And they lived in a region where to this day fortunes rise and fall according to who can gain access to–and control of– this vital resource.

Lonnie Bunch: Allensworth, as a community, was really in an area where water was key. And when the land was acquired, they were promised that there would always be pumps, and there would always be the kind of level of water they needed. And that failed.

Caroline Collins: In fact, as early as 1913–just five years into the town’s founding they faced their first extensive threat to their irrigation water source when the Pacific Farming Company acquired the region’s water supply from the previous welling company. Then it attempted to refuse selling water to the Black residents of Allensworth, who sued.

The residents won their case, but only after expending time, money, and enduring the loss of critical water while they fought it out in court.

Lonnie Bunch: Once the water started to go, that called into question their ability to farm.

Caroline Collins: And the town’s water crisis wasn’t their only looming challenge.

Lonnie Bunch: They also made a business of being a depot station, where the farmers from the local area would come to put their crops, because the Santa Fe railroad train would go through there. But the farmers complained that they had to deal with these Black people, and ultimately, a spur was created to bypass – for the railroad to bypass Allensworth, that took some of the business away.

Caroline Collins: Then, tragedy struck. Just six years after the town’s founding, Colonel Allensworth unexpectedly died when crossing a street in Monrovia in Los Angeles County.

(Pensive orchestral music)

Lonnie Bunch: When the colonel was killed in – run down by a motorcycle in 1914, suddenly the community doesn’t have the bearings it once had.

–Small Pause–

Caroline Collins: Initially, the town still managed to prosper even after Col. Allensworth’s death by pivoting their marketing efforts. They started recruiting residents interested in relocating to California for health and political reasons. They also advertised to veterans because they were attracted to Col. Allensworth’s past military experience. But by the late 1920s, already besieged by racist efforts, which coincided with growing industrialization and urbanization, Allensworth began to decline.

A lot of the town children started to move away, joining nationwide trends like moving to cities and getting jobs in factories and other industrial fields. Also, even though a new company eventually took over the colony’s wells, the township continued to face massive drought, rising arsenic levels, and regional water consolidation by powerful industry titans like the Central Valley’s cotton king, J.G. Boswell. It was a set of conditions that was hard to negotiate. And so, by the Great Depression, the town had dwindled due to its many challenges.

Though most left the town, it was never completely abandoned. And to commemorate its history, in 1976 Col. Allensworth State Historic Park was established on its 260 acres.

–Small pause–

(Music ends)

Caroline Collins: The state historic park wasn’t Allensworth’s only lasting legacy. By the 1920s, the Southern California rural town of El Centro, located near the U.S. / Mexico border was viewed by many as a successor to Allensworth.

Though not technically an all-Black town, the African American enclave of El Centro became a hub for African American opportunity–especially for educators. William Payne, who was also one of the founders of Allensworth, re-settled in El Centro. There, he became the principal of Dunbar Elementary and then Douglass High School where he helped provide an important training ground for Black teachers in California who, because of discrimination, were denied valuable classroom experience by Wwhite districts, and then told they didn’t have enough experience to be hired.

African American teachers received the classroom experience they were deprived of gaining elsewhere. For example, Ruth Acty, because of the opportunities extended to her in El Centro, became the first African American teacher hired by the Berkeley Unified School District in 1943–an achievement indirectly connected to the legacy of Allensworth.

–Reflective pause–

CONCLUSION

Caroline Collins: When thinking about the history of Allensworth, it’s hard not to focus on all the promise that wasn’t fulfilled. And the extraordinary measures that many took to thwart these settlers’ California Dream. Think about it. The Pacific Water Company refused to provide Allensworth citizens with the basic need of water. And the Santa Fe Railroad built a spur line–or a small branch line–just to bypass Allensworth so Wwhite farmers wouldn’t have to do business with the town and use their depot. Those were significant efforts that state historical narratives need to include and reckon with.

But, taking the time to reflect on Allensworth also highlights other important parts of California history. For example, Allensworth and other Black Towns help shine a light on Black people’s long standing relationship to ‘back to land’ movements that are often viewed as very recent and very Wwhite. And in doing so, Allensworth also reminds us of the power of the Black imaginary–even in the midst of structural inequality. Or as Lonnie Bunche puts it–

Lonnie Bunche: And in some ways, its greatest impact is that the people that once lived there became people who believed in education, believed in change, believed that they could make America better.

Caroline Collins: In many ways, the Black communities across rural California that we’ve discussed in these past two episodes still provide valuable examples for us, even today as Black folks across the state and nation continue to face systemic barriers and bias when going about their daily lives like the people of Allensworth who just wanted to make a home, a community, and a just society for themselves and their families.

Dr. Ashley Adams frames this inspiration this way:

Ashley Adams: Places like Allensworth provide us with a model and example of trying to progress and work together to move forward. And we need that today. We need to know that that’s what our ancestors had in mind for us is to work together and to support each other.

Caroline Collins: And so, she focuses on what these settlers did accomplish against seemingly insurmountable odds.

Ashley Adams: There’s a lot that we can learn from the Allensworth settlers because not only did they build the town, but they struggled, you know, and were challenged setting it up and they overcame those challenges and it’s inspiring.

(Cal Ag Roots Theme Music, upbeat jazz hip-hop fusion)

Caroline Collins: The legacy of these Black ‘back to land’ movements in California continued into the modern age. Even in urban areas, where many African Americans brought agricultural practices to city living. And today, Black farmers continue to cultivate the land in rural California. To learn more about these modern practices, tune in to our sixth and final episode, “Still Here: Black Farmers & Agricultural Stewardship in the Modern Age.”

Caroline Collins: Thanks for listening to the Cal Ag Roots podcast. If you liked what you heard, you can check out other stories like this one at www.agroots.org, or on Apple Podcasts. And by the way, if you subscribe and rate this show on Apple Podcasts, it will help other people discover it.

Now some important acknowledgements: We Are Not Strangers Here is a collaboration between Susan Anderson of the California African American Museum, the California Historical Society, Exhibit Envoy and Amy Cohen, myself–Dr. Caroline Collins from UC San Diego, and the Cal Ag Roots Project at the California Institute for Rural Studies.

Our traveling exhibit banners were written by Susan Anderson, our project’s Primary History Advisor. And this podcast was written and produced by me with production help from Lucas Brady Woods.

This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities (Visit calhum.org to learn more), and the 11th Hour Project at the Schmidt Family Foundation.

And finally, special thanks to NPR’s News & Notes for the use of their audio of Lonnie Bunche in this episode and to scholar Delores Nason McBroome for her detailed research on Allensworth which helped us tell this story.

–End of Episode–

Cal Ag Roots Supporters

Huge THANKS to the following generous supporters of Cal Ag Roots. This project was made possible with support from the 11th Hour Project of the Schmidt Family Foundation and California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Episode 4: Independent Settlements: Building Black Communities in Rural California

Starting as early as the 19th century, Black communities–large and small, loosely organized and formal took shape across rural California. Discover the undertold history of California’s Black rural settlements including how these communities represent the tension between the promises and the challenges of living in the Golden State.

Music Credits for Episode 4: “Strange Persons” by Kicksta; “Summer Breeze” and “Inward” by HansTroost; Over the Water, Humans Gather by Dr. Turtle; and The Fish Are Jumping by deangwolfe. Tribe of Noise licensing information can be found here: prosearch.tribeofnoise.com/pages/terms

You can listen online, or better yet, you can subscribe to the podcast so you don’t miss an episode.

Never miss an episode — subscribe today:

Transcript We Are Not Strangers Here Episode 4

“Independent Settlements: Building Black Communities in Rural California”

(Guitar folk music)

Caroline Collins (Narrator): California’s settlement story often highlights rugged individuals: gold panners, homesteaders, laborers. Hardy souls that helped shape rural spaces through tenacity and grit. But these pioneers didn’t make the state what it is today on their own.

In other words, if rural settlers intended to make the Golden State their home, they had to navigate the challenges–and the opportunities–of not just working, but living on the land.

And that often meant going about the work of building communities.

Because a settler’s success in rural California often depended upon the relationships that these miners, ranchers, and farmers formed with each other.

These rural settlements were especially important for many Black settlers across the state who–while seeking opportunity in California–often faced structural inequality. So some Black settlers established roots in rural California by forming communities with one another.

Michael Eissenger: And so in every period of California history, African Americans are making an impact on the landscape as in these communities.

Caroline Collins: Making an impact by not just choosing to settle in California, but by supporting one another’s dreams of forging independent lives in the state. Like in the community of South Dos Palos…

Joe Marshall: Everything in South Dos Palos, except for a few places like behind us, was owned by Black people.

Caroline Collins: So, in this episode and the next, we’re going to take a closer look not just at individual Black settlers in rural California, but the rural communities and settlements some of them founded across the Golden State.

(Music ends)

Places that in some ways, helped make California home for many early Black settlers.

(Cal Ag Roots Theme Music, upbeat jazz hip-hop fusion)

Caroline Collins: I’m Caroline Collins and this is the Cal Ag Roots podcast. Cal Ag Roots is unearthing stories about important moments in the history of California farming to shed light on current issues in agriculture. This is the fourth episode in our We Are Not Strangers Here series. This series, which draws its name from writer Ravi Howard, highlights hidden histories of African Americans who have shaped California’s food and farming culture from early statehood to the present.

This six-part series is also connected to a traveling exhibit with the same name. The exhibit was originally designed to travel throughout California–we printed big, beautiful banners full of all kinds of photos from the archives that accompany the stories we’re telling. But then, the pandemic happened. And so, now we’re digitally reconceiving the We Are Not Strangers Here exhibit so that people can still enjoy it even during the pandemic. It’s not up yet, but we’re working on it. Please check out www.agroots.org for updates.

(Music ends)

Caroline Collins: In the next two episodes, when we talk about Black settlements in California we’re talking about places where Black folks live together–and places that they often established themselves.

These places are important to discuss not just because they aren’t often included in official state narratives. But they’re also important because they represent the tension between the promises and the challenges of living in the Golden State–a tension that, in many ways, still exists today.

Starting as early as the 19th century, these Black communities–large and small, loosely organized and formal took shape across California. They developed for a mixture of reasons from proximity to employment, to settler preference, to exclusionary practices that banned or discouraged Black people from settling in other areas.

The most well-known of these settlements is probably Allensworth, a Black town in Tulare County forty miles north of Bakersfield. It was founded in 1908 by a group of settlers led by the town’s namesake: Col. Allen Allensworth. And so in the next episode, we’re going to dive into the history and the legacy of Allensworth.

However, when we spoke to our podcast’s primary History Advisor, historian Susan Anderson, to get a sense of the scope of these communities–she reminded us to keep an important fact in mind.

Susan Anderson: Allensworth wasn’t the only all Black settlement. California was just dotted by dozens of them.

Caroline Collins: Which means that telling the story of Black settlements in rural California means looking beyond Allensworth to the breadth and diversity of African American communities.

Because these independent settlements came in various shapes and sizes and contexts. Some were small enclaves where a cluster of Black pioneers settled in the same general area. Others began as labor camps where Black agricultural workers lived together, eventually forming more permanent and substantial communities. And some, like Allensworth, were founded as quote: All-Black Towns, meaning these townships were at least 90 percent Black and made up of residents all seeking to determine their own political destiny.

Susan Anderson: They had varying degrees of intentionality, but they all were people exercising their choice to live in these Black communities.

Caroline Collins: And nearly all of them…were in rural California from the woodlands near the Oregon border to the mountains of rural San Diego County, and especially in–

Susan Anderson: the central Valley because they were all farming communities.

Caroline Collins: Some were formed decades before the Allensworth founders ever laid eyes on their future settlement…

–Reflective pause–

(Ragtime music)

Caroline Collins: If you walk along Main Street in the San Diego County mountain town of Julian–or ride in one of its horse-drawn carriages–the town may seem like it’s stopped in time. Featuring Old West architecture, its quaint storefronts sell various wares, souvenirs, and piping hot servings of the town’s famous apple pies.

At the corner of Main and B Street, across from the Julian Cider Mill and the town hall, you’ll find a California institution–the two-story Julian Gold Rush Hotel, the longest continuously operating hotel in the entire state.

Originally named The Hotel Robinson, this historic site was built in 1897 by Margaret Tull Robinson and her husband, Albert Robinson. Famous for its hospitality and its meals, the hotel was known for catering to well-heeled guests, including wealthy families and congressmen.

Margaret, who hotel employees described as “prim and energetic” yet “quiet-spoken,” was the daughter of Jesse Tull, the first Black man summoned as a juror in San Diego County. Her mother Susan Tull, was a landed Black woman historians believe may have financed the construction of the hotel. And Margaret’s husband Albert, who’d formerly been enslaved in Missouri, had first worked in the area as cook at a local ranch. Together, the Robinsons opened one of the first establishments in San Diego County to be owned and operated by African Americans.

(Music Ends)

Caroline Collins: When considering the broader historical context of the Robinsons’ endeavor, their Julian location makes sense. Decades before the Robinsons built their hotel, Black and Native American people were already settled in the area. According to the San Diego County History Center, most local African Americans in this period felt rural areas offered more economic advantages than city life. And so, by the end of the 19th century, when the Hotel Robinson opened, the majority of San Diego County’s Black residents lived in Julian.

In fact, it was a Black settler that triggered Julian’s eventual population boom.

–Small pause–

(Guitar folk music)

Caroline Collins: It all started in the winter of 1869. African American cattle rancher A.E. Coleman, who also went by Fred, lived in the mountainous region surrounded by pine-oaks with his wife Maria Jesusa Nejo, a native Kumeyaay woman, and their children.

One day, while watering his horse at a local creek just west of what would become the Julian township, Coleman noticed a glimmer in the water. He crouched down closer and discovered…it was gold. Coleman was a veteran of the Northern California gold rush. So, like other African Americans that had toiled in the goldfields, he was already an experienced miner. Which means, he didn’t just know how to expertly pan for the gold dust he saw glistening in the creek. We can assume he was also familiar with the many ways to capitalize on an impending rush for gold. In fact, according to the Journal of Economic History, during the Northern California Gold Rush it was the merchants that made far more money than most of the miners actually did.

With this knowledge most likely in mind, Coleman built a wagon toll road from nearby Santa Ysabel to what’s now called Coleman Valley. It was a calculation that paid off when–within weeks–a tent city shot up after over 800 prospectors descended upon the area seeking access to the goldfields. Access they got by way of Coleman’s toll road. By 1870, just months later, a full blown gold rush had begun.

The creek where Coleman found the gold was renamed Coleman Creek, and soon he helped establish the Coleman Mining District. He was elected its first recorder, meaning, if a speculator wanted to file a claim to mine land within the district, Coleman would process and record that claim. Miners working in the district never made substantial gains — other more prosperous districts eventually formed.

But the result of the rush was clear. The area soon grew, attracting pioneers of various backgrounds but including more African American settlers like America Newton, an entrepreneur who was born enslaved in Missouri. She started a laundry enterprise and eventually purchased an 80 acre homestead in Julian. Black settlers Ernest Morgan and Elvira Price also arrived and soon they owned and operated Julian’s Bon Ton Restaurant. Issac Atkinson, another Black settler, owned a bakery. The gold rush also drew Jesse and Susan Tull and their soft-spoken daughter Margaret to the area. And as we now know, Margaret would marry Albert Robinson, who also joined this community in the mountains of San Diego county. And together the Robinsons built their famous hotel. Today it’s a national and state historic landmark still surrounded by the cedar and locust trees Albert planted more than a century ago.

–Reflective pause–

(Music Ends)

Caroline Collins: Rural settlements like Julian across the state reflect California’s changing history. For example, as agricultural methods changed so did migration patterns and the communities that were formed by arriving settlers. One of these shifts occurred as California’s agricultural industry expanded.

Like other migrants to California, many African Americans made their start in the state in its agricultural fields. In fact, starting as early as 1888, large-scale growers began recruiting Southern Black workers to harvest fruits, vegetables, and cotton in the Central and Imperial Valleys.

Michael Eissenger: And there were articles in the New York times or articles in the Atlanta journal. Papers all recruiting for African Americans to come to California.

Caroline Collins: That’s Dr. Michael Eissenger, he studies historically African American rural settlements in central California.

Michael Eissenger: And then when they got here, many of them could go across the street to another farm or if they had skills, carpentry skills, skills tanning leather, skills at butchery, they could find better work at better pay.

Caroline Collins: So, these workers could leverage their skills in the state. But unlike earlier Black rural settlers, most of them hadn’t come to California to individually homestead and work land that they owned and lived upon. That means making the long trek to California and finding work in its fields was the just the beginning of their settlement stories. They still needed a place to live.

This led to the birth of communities that were organized around the recruitment of Black labor. Places where newly arriving workers could be close to jobs. For example, in 1907 a colony of farmworkers was created near the cotton fields of Kern County. It became the community of Wasco.

And some African American communities also sprung up around other rural trades, like the lumber industry. In the 1920s, one such community developed in Siskiyou County in the town of Weed, near the Oregon border.

Caroline Collins: Mark Oliver chronicles this settlement and others in his 2011 documentary From the Quarters to Lincoln Heights. It tells the story of how a large African American population rooted themselves in lumber towns like Weed.

(Ragtime music)

In the film Mildred Jacobs, Al Bearden and Melvin Smith recall how a small labor camp for the Long-Bell Lumber Company eventually grew in the town of Weed. At first, it was the lumber company itself that lured Southern workers to this far northern destination.

Mark Oliver film clip: voice # 1 (Mildred Jacobs, Redding CA): Long Bell brought a lot of people from Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas and different places to Weed. They just moved them out here.